The strange thing is that Rudolf Nureyev was just a ballet dancer at a time when the world in general paid little attention to what was regarded as an elite art form. But Nureyev was no mere dancer. He revolutionised ballet. His presence brought it into the evening news programmes and onto the front pages of newspapers.

This year has seen two films about his life and times. Earlier in the year the Ralph Fiennes directed movie “The White Crow” arrived in cinemas. This concentrates on Nureyev’s early years leading to his arrival at the most famous ballet company in the world, Leningrad’s Kirov Ballet (now renamed the Mariinsky Ballet).

Trailer for “The White Crow”

Six weeks ago a new Hollywood documentary about the star’s life was released. “Nureyev” tells he full story of the young boy from a Tartar Muslim family living in absolute poverty in the old Soviet Union who was determined to become a dancer. Rather like the boy in Stephen Daldry’s popular film and the subsequent musical “Billy Elliot”, Nureyev achieved his dream - but on a truly global stage. For 25 years he was the equivalent of a rock star as no other male ballet dancer in history had been before. Close to the start of the century, the ballet world had lauded the young bisexual Vaslav Nijinsky as the greatest male dancer the ballet world had ever known. The very gay Rudolph Nureyev conquered the entire world.

In the 1950s Soviet Union, there was little for that dictatorship to crow about. As it was preparing to beat the USA by sending the first man into space, its leader Kruschev decided to wield some soft power. The Kirov Ballet in Leningrad was known to be the greatest in the world. So the Soviet authorities decided to permit it to perform in Western Europe.

Preview of a much earlier PBS Documentary about Nureyev in Russia with footage shot by his young German lover

Its 1961 season in Paris was a sensation. The tall, handsome, wild, glamorous, amazingly athletic Nureyev whose leaps made him seem as though floating in the air, became an overnight star. He electrified Paris. Very much a free spirit, the 23-year old loved the freedom he found in the city and wanted to experience all it offered – including its gay bars. He constantly clashed with the KGB minders who always accompanied Soviet performing arts ensembles overseas. At Paris airport as the company prepared to fly on to London, Nureyev was told he would not be accompanying the party. One agent said the Communist Party General Secretary Kruschev wanted him in Moscow for a private performance. When he asked another, he was told his mother was ill. In a flash he realised he was being told lies and was being withdrawn because he did not follow the Party rules. Once back in the Soviet Union, he might never be allowed out again.

It took less than a minute for him to race towards two French police inspectors claiming political asylum. This was the height of the Cold War and Nureyev was the first major very public defection from the Soviet Union. Kruschev was furious. Less than two months later the Berlin Wall was erected.

For a time Nureyev did not know where to live, he could not dance and life must have seemed almost as miserable as in the Soviet Union. After a spell with a small ballet company, he was offered guest engagements in Copenhagen. There he was determined to meet the man whom the New York Times critic dubbed “the greatest male classical dancer of his time,” Erik Bruhn. Nine years his senior. Nureyev had adored Bruhn’s dancing from afar. During that first meeting, they fell in love.

Erik Bruhn with his lover, the young Nureyev

Their love affair was to last almost 18 years. Even after Nureyev met and fell in love with a much younger dancer, Bruhn remained the love of Nureyev’s life until he died in 1986 aged 57. During both relationships, Nureyev was highly promiscuous, continuing to enjoy one-night stands with all manner of young men, often rough trade.

Soon Nureyev was to set up home in London as a leading soloist with the Royal Ballet. It was there he met the company’s prima ballerina, Margot Fonteyn, when they danced in “Giselle” together. At that time nearing what everyone thought was the end of her illustrious career, the partnership with the 24-year old Nureyev gave the 43-year old Fonteyn a completely new lease on life. Their on-stage chemistry was stunning and the professional partnership became the talk of the world. It was to continue for another 18 years.

Trailer for “Nureyev”

Nureyev was the supreme narcissist. He always had to be the star. He was difficult to like. He often flew into tantrums. He had a coterie of female groupies – mostly in their 50s and older whose main criteria, above all, was that they had to adore him and pay for everything. He hated rehearsing and often turned up to learn a role only a few days before its premiere. All he wanted was to be the centre of attention on stage. All the world’s ballet companies wanted him and he danced with most.

Then a dark cloud appeared. This one had no silver lining.

As soon as people started talking in hushed tones about the new plague affecting gay men, Nureyev had a premonition that he was infected with HIV. In 1984 a test proved him correct. Even so he lived for another nine years, for much of that time working at an exhausting pace. Understandably, the illness took a toll on his performances. He undertook a world tour with a selected group of dancers. It was a near disaster. At one performance, members of the audience shouted “Refund! Refund!” It was a sad end for a very proud man.

I only saw him dance once. It was at a performance of “Giselle” with Fonteyn when I was studying in Vienna in the late 1960s. Both were at the height of their artistry. But it is not the athletic leaps or the amazing chemistry between the two dancers that sticks in my mind. It is something far more simple. At the opening of Act II the stage was bare. From upstage Nureyev entered looking for his lover Giselle’s grave. He simply walked slowly along the back and around the stage, a small bunch of lilies in his hands and a very long cape flowing behind him. During the sadness of that walk, an almost animal magnetism captured the entire audience.

Nureyev died of AIDS in 1993 aged 54. The new movie and the documentary have not received the best of reviews. But at the least they remind us what a scintillating dancer and vain personality he was, and yet how he quite literally set the world on fire. As Beatlemania waned, Balletmania had taken over!

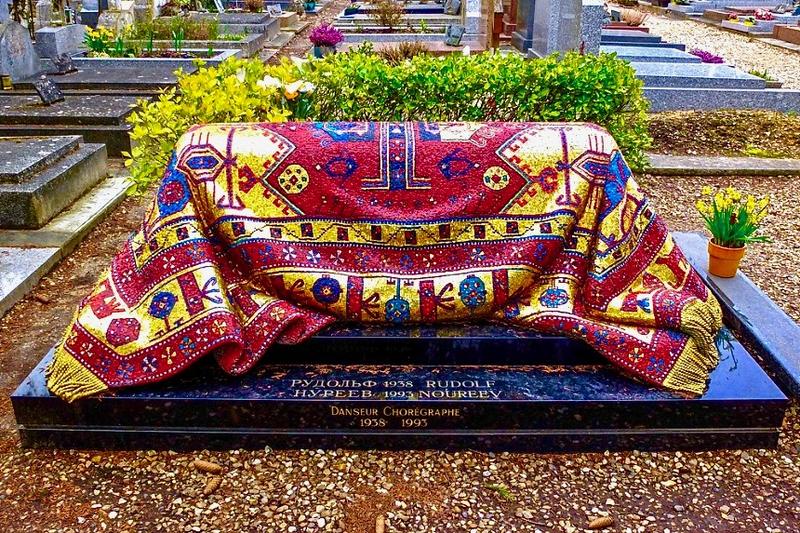

Nureyev’s Tomb in Paris

Photo: Flickr.com